Monday, April 29, 2013

At Last

At Last

Edward St. Aubyn

Although At Last is the fifth and final book of the semi-autobiographical Patrick Melrose cycle, it is perfectly readable as a stand-alone novel.

Like the previous Melrose novels, At Last is narrated around a single event in the life of Patrick Melrose. Fittingly for the final installment of a series, this time the event is a funeral. Patrick Melrose’s mother, Eleanor, a damaged, deranged heiress, has died at last, and although no one at the funeral (Patrick included) appears to miss her very much, the rites and rituals of death cause Patrick to revisit the history of his horrendous family and the unhappy events that formed him. One by one, the spoiled, miserable, mostly very rich aristocrats in Patrick’s life drift through the funeral: his wife, his children, his mistress, a battery of cousins, the acerbic Nicholas Pratt, Eleanor’s batty spiritual advisor, Annette. Their condolences are mostly hollow, and over the course of the novel we find out why Patrick is capable of statements like, “I think my mother’s death is the best thing to happen to me since…well, since my father’s death.”

At Last finds Patrick not long after he has completed an extended stay at the Priory (a rehabilitation centre for extremely rich people), where he has overcome the temptations of both alcohol and of Becky, a lovely young drug addict. The reason for Patrick’s alcoholism becomes quickly apparent as we learn that Eleanor spent the first act of her life married to a sadistic pedophile, Patrick’s father David, and the second act atoning for it by becoming a professional benefactress, giving away her fortune to everyone except for her son: casual acquaintances, mystical religions, South American priests-cum-pedophiles.

Patrick passed his taciturn, terrified childhood in Saint-Nazaire in France and at a grand estate pile in England, where he was sexually abused at age five by his father with the tacit consent of his wilfully blind mother ("How could Eleanor not have known?" he rages). Robbed of his innocence, he is subsequently also robbed of his inheritance when Eleanor disinherits him in favour of the “Transpersonal Foundation,” an institution dedicated to dubious practices of all shades, including “shamanic healing.”

At Last offers a darkly humorous glimpse into the lives of the titled British upper class, and the book is vaguely reminiscent of Pride and Prejudice in its fascination with inheritance. Both David and his mother were reared in the trappings of wealth, only to have it all snatched away and then miraculously gifted back by a chance clause in some distant relative’s will.

The fascination of At Last is not in its plot, which after all revolves around a funeral. In the hands of a lesser author, this book would be very dull: a confessional, a pity party for the rich in which all of the action transpires solely in the narrator’s head. There is no danger of this, however, as the novel is exquisitely written. St. Aubyn makes the mundane sequence of a funeral interesting by employing an economy, precision, and wit in his writing that is reminiscent of J. M. Coetzee or Muriel Spark. There are no superfluous passages, no bloated walls of text; every adjective is precisely positioned. It would be hard to call At Last an enjoyable read—the subjects are too macabre, and Patrick’s life is a train wreck. But like all train wrecks, it’s hard to look away from it.

- Monika Yazdanian

Travels with Epicurus

Travels with Epicurus: A Journey to a Greek Island in Search of a Fulfilled Life

Daniel Klein

This is a delightful little book! A well-written and witty travelogue, it captures the idyllic character of a Greek island. But it is much more than a travelogue; it captures the essence of life itself.

Armed with a bag of philosophy books, the 73-year-old Klein returns to Greece and to the island of Hydra to contemplate life in old age. Here, he is able to peruse the writings of Epicurus and other philosophers, both ancient and modern, as he attempts to find answers to guide him through his remaining years, to become “a fulfilled old man.”

Epicurus (341 to 270 BCE) considered that the highest good of life is pleasure, and that old age is the pinnacle of life, providing a unique chance for unbounded, wide-ranging thought. “When a man is old he may be young in good things through the pleasing recollection of the past.”

But Epicurus was no hedonist. He was convinced that mental pleasures exceed physical pleasures. His views on sex can only be described as prudish.

He did not believe in an afterlife, and was not afraid of death. “Death is nothing to us, since when we are, death has not come, and when death has come, we are not. Death is no more alarming than the nothingness before birth."

Klein’s favourite haunt on Hydra is Dimitri’s Taverna, where he loves to eavesdrop on the conversations among an interesting group of older Greek men sitting at Tasso’s table. And he ends his month on Hydra enjoying Easter dinner with Tasso and his family.

On a visit to an old age home on the mountainside above the town, he meets Spyros, a senile and incontinent old man in his 90s, an encounter that affects Klein deeply. He falls back on the Roman philosopher Seneca: “Dying well means escape from the danger of living ill.” But, Klein asks, how do we know when we must “escape?”

- D’Arcy McGee

The Smart One

The Smart One

Jennifer Close

Jennifer Close has perfectly depicted the stress and chaos of returning to live at home as an adult. Written from the perspectives of four different women, The Smart One removes readers from the comfort of rooting for a single protagonist and instead shifts constantly between college-going Cleo, the slightly neurotic Martha, over-worrying Weezy, and debt-ridden Claire.

The Smart One attempts to avoid the stereotypes of mindless chick lit and focuses on issues that are more realistic than shopping and man-troubles. The characters’ challenges still fall firmly in the “first-world problems” category, but the shift from shopaholics and broken-hearted damsels is a welcome one. The characters, however, seem to lack the ability to think optimistically about anything, and I found myself nearly burned out from their constant complaints throughout the second part of the novel.

The solid writing and multiple characters with well-developed personalities do make the book an easy read—just don’t expect a fairy tale or 300 pages of diamond rings and shiny things.

- Katie Ryan

Jennifer Close

Jennifer Close has perfectly depicted the stress and chaos of returning to live at home as an adult. Written from the perspectives of four different women, The Smart One removes readers from the comfort of rooting for a single protagonist and instead shifts constantly between college-going Cleo, the slightly neurotic Martha, over-worrying Weezy, and debt-ridden Claire.

The Smart One attempts to avoid the stereotypes of mindless chick lit and focuses on issues that are more realistic than shopping and man-troubles. The characters’ challenges still fall firmly in the “first-world problems” category, but the shift from shopaholics and broken-hearted damsels is a welcome one. The characters, however, seem to lack the ability to think optimistically about anything, and I found myself nearly burned out from their constant complaints throughout the second part of the novel.

The solid writing and multiple characters with well-developed personalities do make the book an easy read—just don’t expect a fairy tale or 300 pages of diamond rings and shiny things.

- Katie Ryan

Monday, April 22, 2013

The Long Earth

The Long Earth

Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter

My wife commented the other day that she didn't think I liked much in the way of science fiction. This isn't entirely true, although I'm less inclined to the science fiction imaginings of outer space, ray guns, and spaceships or the fantastical worlds of dragons and elves. What I particularly enjoy are books that take our own world and re-imagine it in subtle but thought-provoking ways.

The Long Earth is such a book. Written as a partnership of Terry Pratchett (he of the ever-expanding Discworld series) and Stephen Baxter (an almost-as-prolific author who likes his science fiction to have a hard scientific basis), the book reconceives what it means to travel in time and space. What if we lived in a world that had multiple instances—ones that we could visit with a device we could build ourselves, fabricated from simple electronics and powered by a potato? (And yes, you can.) What if you could visit, inhabit, or colonize an endless series of plausible worlds? Or if you could, with time, travel to the very ends of what “plausible” looks like?

While there is less immediate evidence of Terry Pratchett's unique brand of humour (in Discworld, it may be turtles all the way down; here, it's worlds all the way across), there is much to enjoy in this book. What I particularly appreciate is the way in which Baxter and Pratchett start with a simple conceptual possibility and progressively unfold deeper layers of meaning. In particular, they explore the larger implications of what such a possibility would mean for society, and they reimagine quantum entanglement and the collective unconscious in a uniquely ingenious manner that pokes around the edges of the question, "Why are we here?" If you like your science fiction to be both plausible and mind expanding, this is your book.

Here is a collage of readers (including some well-known authors) reading the beginning of The Long Earth:

- Mark Mullaly

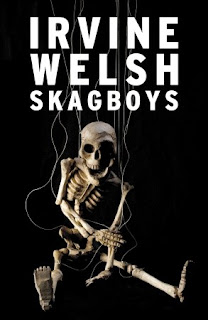

Skagboys

Skagboys

By Irvine Welsh

The Edinburgh-based characters Renton, Sick Boy, Spud, Tommy, and Begbie are all back in this tale that documents the early years of their lives and their difficulties with heroin, university, family life, and poverty. Set in the United Kingdom in the mid-1980s, this story is mildly political and full of the dark humor that Welsh is known for. Although it is a prequel to the well-known Trainspotting, Skagboys easily stands as its own masterpiece, in my opinion rivaling the previous books in this series. Unlike other fictional works written about drug addiction that tend to sensationalize drug use, the characters here are complex and humanized by stories that show their steep decline into addiction, petty theft, and, in some cases, violence. Welsh captures the social and political climate of the UK in the 1980s so vividly that it's easy to understand how young people living under Thatcher felt they had no future to look forward to as social programs were cut, jobs were lost, and the cost of a good education soared beyond the reach of the working class. Epidemics of intravenous drug abuse and AIDS were sweeping the Northern UK so voraciously that it's hard to imagine many survivors of from that era, and indeed this story illustrates that among some groups there weren't many.

Rising out of the ashes of the late 1970s punk scene, the characters here are rich and diverse, giving the impression that this book is more a documentation of actual people than a fictionalized story. Like its predecessors, Skagboys is narrated by the characters themselves, all of the dialogue written phonetically to match their thick Scottish accents, so it's easy to feel completely immersed, as if you're amongst the characters yourself. This multi-layered and crisscrossing emotional roller-coaster of a journey that Welsh takes you on has some steep ascents and quick drops; one minute I would be laughing out loud at a prank pulled by Rents and Sick Boy, and the next I would tear up listening to a story describing the physical and psychological abuse some of them suffered as children. All of it paints a picture of the struggles these people endured, individually and collectively.

Skagboys has easily made my top-ten list for literature over the past decade, and I would highly recommend it to anyone that finds any of the aforementioned topics interesting. This massive book spans nearly 550 pages, and although it originally seemed a daunting task to take it on, by the end I wanted more. I'm saving Skagboys in my own personal collection to be read again, whenever I feel inclined to spend time with the scabby boys from Leith.

- Mike XVX

Son

Son

Lois Lowry

Finally, after nineteen years of waiting, Lois Lowry concludes her four-book dystopian series that began with The Giver (A Newberry Medal winner), continued with Gathering Blue and Messenger, and now ends with Son, a heart-wrenching tale of a mother searching in vain for her child. The Giver series is set in a society that has eliminated pain and conflict by enforcing “Sameness,” a strict conformity to social roles and a repression of unruly emotions and desires. In The Giver, Jonas becomes the receiver of memory for his community, but he ends up questioning the life the community offers and becoming attached to Gabriel, a baby who fails to thrive and so is marked for “release.” I remember reading The Giver when I was younger and wondering what would happen to Jonas and Gabe, despite the fact I barely understood their confusing way of life. Son travels back to the beginning of the story and we get to watch the familiar events take place, but through the perspective of another young person, Claire. If you liked The Giver and wondered about its conclusion (like me) then you will enjoy Son.

Claire is fourteen years old, has grown up in the same world as Jonas, and has equally suffered. After she has a problematic time giving birth, Claire’s son is taken away and she is discharged as a Birthmother and sent to work in the fish hatchery. But something is not right with Claire; she feels emotions that are unusual, given the Sameness that rules her community. Claire falls in love with her son, whom she secretly visits at the nurturing centre, and feels apathetic toward her job. But when Jonas leaves, all is thrown into chaos, and Claire finds her way onto a ship that takes her far away from her home. After she falls off the ship during a storm, she wakes in a new world with her memory gone. Slowly, Claire regains her memory and a strong yearning for her son. Old and new threads are picked up and woven together as we follow Claire's heroic journey to reunite with her child.

- Madelle Krucker

Lois Lowry

Finally, after nineteen years of waiting, Lois Lowry concludes her four-book dystopian series that began with The Giver (A Newberry Medal winner), continued with Gathering Blue and Messenger, and now ends with Son, a heart-wrenching tale of a mother searching in vain for her child. The Giver series is set in a society that has eliminated pain and conflict by enforcing “Sameness,” a strict conformity to social roles and a repression of unruly emotions and desires. In The Giver, Jonas becomes the receiver of memory for his community, but he ends up questioning the life the community offers and becoming attached to Gabriel, a baby who fails to thrive and so is marked for “release.” I remember reading The Giver when I was younger and wondering what would happen to Jonas and Gabe, despite the fact I barely understood their confusing way of life. Son travels back to the beginning of the story and we get to watch the familiar events take place, but through the perspective of another young person, Claire. If you liked The Giver and wondered about its conclusion (like me) then you will enjoy Son.

Claire is fourteen years old, has grown up in the same world as Jonas, and has equally suffered. After she has a problematic time giving birth, Claire’s son is taken away and she is discharged as a Birthmother and sent to work in the fish hatchery. But something is not right with Claire; she feels emotions that are unusual, given the Sameness that rules her community. Claire falls in love with her son, whom she secretly visits at the nurturing centre, and feels apathetic toward her job. But when Jonas leaves, all is thrown into chaos, and Claire finds her way onto a ship that takes her far away from her home. After she falls off the ship during a storm, she wakes in a new world with her memory gone. Slowly, Claire regains her memory and a strong yearning for her son. Old and new threads are picked up and woven together as we follow Claire's heroic journey to reunite with her child.

- Madelle Krucker

Monday, April 15, 2013

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema

Cory Doctorow

Have you ever enjoyed an online video remix made using TV or movie clips? Pirate Cinema, by award-winning author Cory Doctorow (Little Brother, Boing Boing), is set in a near-future United Kingdom where big media fights to outlaw all forms of copyright infringement with stifling legal penalties. Teenage protagonist Trent McCauley's dedication to creating remix videos causes him to run afoul of these laws. His punishment is the disconnection of his family's Internet, severing their ability to get health care, education, and work. Ashamed, Trent flees to London, banding together with an underground group of squatters and social misfits—all the while starting a revolution that will re-take the right to create new media.

Pirate Cinema is an entertaining and fast-moving allegory about the struggle to find balance between copyright and personal freedom.

- Dana Rea

Cory Doctorow

Have you ever enjoyed an online video remix made using TV or movie clips? Pirate Cinema, by award-winning author Cory Doctorow (Little Brother, Boing Boing), is set in a near-future United Kingdom where big media fights to outlaw all forms of copyright infringement with stifling legal penalties. Teenage protagonist Trent McCauley's dedication to creating remix videos causes him to run afoul of these laws. His punishment is the disconnection of his family's Internet, severing their ability to get health care, education, and work. Ashamed, Trent flees to London, banding together with an underground group of squatters and social misfits—all the while starting a revolution that will re-take the right to create new media.

Pirate Cinema is an entertaining and fast-moving allegory about the struggle to find balance between copyright and personal freedom.

- Dana Rea

The Spark

The Spark: A Mother’s Story of Nurturing Genius

Kristine Barnett

This will pretty much have to be the feel-good story of the year. The author’s son, Jacob, was relatively normal for the first fourteen months of his life, but then began to withdraw into himself. At age two he was diagnosed as autistic (specifically, Asperger’s syndrome) and the “experts” said that he would never read but might, perhaps, learn to tie his own shoes by the time he was sixteen. His mother never gave up on him, however, and the story of her therapy for him is heartwarming. By the time he was eight he had left elementary school and was at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis taking advanced astrophysics classes. At age twelve he became a paid researcher in quantum physics and co-authored a paper.*

In the midst of dealing with his autism, the family was beset with many other problems—health issues, financial setbacks, death in the family. All are dealt with by grit, determination, and love. Truly, the only sad part of the whole saga is trying to find out what he’s up to these days by googling his name and wading through the negative comments small minds are contributing to the discussions.

- Steve Lidkea

* For anyone interested, see Yogesh N. Joglekar, Jacob L. Barnett, "Origin of maximal symmetry breaking in even PT-symmetric lattices." The abstract is as follows:

By investigating a parity- and time-reversal- (PT-) symmetric, N-site lattice with impurities ±iγ and hopping amplitudes t0 (tb) for regions outside (between) the impurity locations, we probe the interimpurity-distance dependence of the critical impurity strength and the origin of maximal PT-symmetry breaking that occurs when the impurities are nearest neighbors. Through a simple and exact derivation, we prove that the critical impurity strength is equal to the hopping amplitude between the impurities, γc=tb, and the simultaneous emergence of N complex eigenvalues is a robust feature of any PT-symmetric hopping profile. Our results show that the threshold strength γc can be widely tuned by a small change in the global profile of the lattice and thus have experimental implications.

Check out Jacob's TEDxTeen talk:

Kristine Barnett

This will pretty much have to be the feel-good story of the year. The author’s son, Jacob, was relatively normal for the first fourteen months of his life, but then began to withdraw into himself. At age two he was diagnosed as autistic (specifically, Asperger’s syndrome) and the “experts” said that he would never read but might, perhaps, learn to tie his own shoes by the time he was sixteen. His mother never gave up on him, however, and the story of her therapy for him is heartwarming. By the time he was eight he had left elementary school and was at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis taking advanced astrophysics classes. At age twelve he became a paid researcher in quantum physics and co-authored a paper.*

In the midst of dealing with his autism, the family was beset with many other problems—health issues, financial setbacks, death in the family. All are dealt with by grit, determination, and love. Truly, the only sad part of the whole saga is trying to find out what he’s up to these days by googling his name and wading through the negative comments small minds are contributing to the discussions.

- Steve Lidkea

* For anyone interested, see Yogesh N. Joglekar, Jacob L. Barnett, "Origin of maximal symmetry breaking in even PT-symmetric lattices." The abstract is as follows:

By investigating a parity- and time-reversal- (PT-) symmetric, N-site lattice with impurities ±iγ and hopping amplitudes t0 (tb) for regions outside (between) the impurity locations, we probe the interimpurity-distance dependence of the critical impurity strength and the origin of maximal PT-symmetry breaking that occurs when the impurities are nearest neighbors. Through a simple and exact derivation, we prove that the critical impurity strength is equal to the hopping amplitude between the impurities, γc=tb, and the simultaneous emergence of N complex eigenvalues is a robust feature of any PT-symmetric hopping profile. Our results show that the threshold strength γc can be widely tuned by a small change in the global profile of the lattice and thus have experimental implications.

Check out Jacob's TEDxTeen talk:

Children of the Jacaranda Tree

Children of the Jacaranda Tree

Sahar Delijani

Children of the Jacaranda Tree is a gripping novel that unfolds over three decades in post-revolutionary Iran. It begins with the birth of a baby girl inside the walls of the infamous Evin prison. The book follows her, her cousins, and her friends—all children of political prisoners—as they are raised amid the turmoil and tyranny of the Iranian regime that took power after the revolution. As they move through life, each child struggles to come to terms with the traumas that his or her parents were forced to endure in their efforts to bring change to their beloved country. Each step of the way the characters’ lives reflect the turbulence and bewilderment engulfing the nation.

Written with a compelling rawness and honesty, Delijani’s novel makes the reader feel the emotions of every horror and triumph experienced by the characters. The pain of loved ones lost, the fear of unpredictably ruthless authorities, and the undying hope of a better future all exist simultaneously within the hearts of each of the characters. With descriptions that are as rich and vivid as they are clear and simple, Sahar Delijani not only invites you to watch a host of intriguing characters, she allows you to become them.

- Elisa Cooper

Monday, April 8, 2013

Dear Life

Dear Life

Alice Munro

My first encounter with Alice Munro’s writing was thanks to a class assignment. By then her first collection of stories was already a decade old and had won the Governor General’s Award for Fiction. I remember that the stories held my interest but also that they made me uncomfortable. I kept the book on my shelf after many others from that period had been given away, but I didn’t return to her writing until long after graduation when one of my favourite professors came for sherry. He’s a Southern gentleman of impeccable manners who will take a little sherry “to celebrate,” and in our broad-ranging conversation, he declared Munro the greatest Canadian writer. I still didn’t go back to that first book, Dance of the Happy Shades, but I have bought and devoured everything she’s written since.

When one reads Munro’s entire body of work, there is a seamlessness and a consistency to her writing that makes it seem as if she wrote them all at one time, at the top of her career. Early stories and the latest ones are all of a piece, to put it in Munro County language. No wonder she won the Man Booker International Prize in 2009 for her lifetime body of work, or that she is a three-time winner of our Governor General’s Award for Fiction. Wikipedia points out that she is a perennial contender for the Nobel Prize, and often called Canada’s Chekhov.

As consistently satisfying, discomfiting, and even addictive as Munro’s stories are across her large body of work, Dear Life contains a surprise. The final sixty-two pages form a separate unit, one Munro says is “autobiographical in feeling, though not, sometimes, entirely so in fact.” I was profoundly affected by the clear Munro voice, stopping readers in their tracks to mark a change and then continuing with a rather chilling, “I believe [these chapters] are the first and last—and the closest—things I have to say about my own life.” And it is, indeed, a more sophisticated, knowing voice that continues on for the remainder of the book.

I’ve been imagining Munro behind many of her characters for decades. In school we had to call the narrator of Munro’s stories the “putative Munro” to indicate we knew the teller wasn’t really the same as the author, but that in some writing there were reasons to think the narrator could be assumed to be giving personal information. For Munro to step out from behind her characters and actually speak to us momentarily took my breath away. And when an author changes voice like that, after so many years of doing otherwise, the experience for the reader changes too. In those sixty-two pages, I was simultaneously meeting Munro and constantly making an inventory of how her “dear life” had been portrayed in the hundreds of stories I have read. So her father really did roll his own cigarettes. So she really did have contempt for her mother’s judgemental views of others. The list went on, leading me to wonder if some of the other more disturbing incidents in her stories also came from real events.

But then, that’s what makes Alice Munro such a great writer. It’s also why from the very first story I experienced discomfort. Whether Alice Munro is being autobiographical is beside the point. What she is most certainly doing is showing us aspects of ourselves, reminding us of embarrassing encounters, judgement errors, deceits in our own lives. Also of touching moments and the infinite capacity of some people to express their humanity and to acknowledge yours.

Maybe it’s time to pull Dance of the Happy Shades off the shelf for another read?

- Reg Sauvages

Reginald Sauvages, PhD, is the nom de plume of a local bibliophile (read: bookworm) who goes on building bookshelves and buying paperbacks for the beach so sand doesn’t ruin favourite clothbound books, even while owning an e-reader.

Alice Munro

My first encounter with Alice Munro’s writing was thanks to a class assignment. By then her first collection of stories was already a decade old and had won the Governor General’s Award for Fiction. I remember that the stories held my interest but also that they made me uncomfortable. I kept the book on my shelf after many others from that period had been given away, but I didn’t return to her writing until long after graduation when one of my favourite professors came for sherry. He’s a Southern gentleman of impeccable manners who will take a little sherry “to celebrate,” and in our broad-ranging conversation, he declared Munro the greatest Canadian writer. I still didn’t go back to that first book, Dance of the Happy Shades, but I have bought and devoured everything she’s written since.

When one reads Munro’s entire body of work, there is a seamlessness and a consistency to her writing that makes it seem as if she wrote them all at one time, at the top of her career. Early stories and the latest ones are all of a piece, to put it in Munro County language. No wonder she won the Man Booker International Prize in 2009 for her lifetime body of work, or that she is a three-time winner of our Governor General’s Award for Fiction. Wikipedia points out that she is a perennial contender for the Nobel Prize, and often called Canada’s Chekhov.

As consistently satisfying, discomfiting, and even addictive as Munro’s stories are across her large body of work, Dear Life contains a surprise. The final sixty-two pages form a separate unit, one Munro says is “autobiographical in feeling, though not, sometimes, entirely so in fact.” I was profoundly affected by the clear Munro voice, stopping readers in their tracks to mark a change and then continuing with a rather chilling, “I believe [these chapters] are the first and last—and the closest—things I have to say about my own life.” And it is, indeed, a more sophisticated, knowing voice that continues on for the remainder of the book.

I’ve been imagining Munro behind many of her characters for decades. In school we had to call the narrator of Munro’s stories the “putative Munro” to indicate we knew the teller wasn’t really the same as the author, but that in some writing there were reasons to think the narrator could be assumed to be giving personal information. For Munro to step out from behind her characters and actually speak to us momentarily took my breath away. And when an author changes voice like that, after so many years of doing otherwise, the experience for the reader changes too. In those sixty-two pages, I was simultaneously meeting Munro and constantly making an inventory of how her “dear life” had been portrayed in the hundreds of stories I have read. So her father really did roll his own cigarettes. So she really did have contempt for her mother’s judgemental views of others. The list went on, leading me to wonder if some of the other more disturbing incidents in her stories also came from real events.

But then, that’s what makes Alice Munro such a great writer. It’s also why from the very first story I experienced discomfort. Whether Alice Munro is being autobiographical is beside the point. What she is most certainly doing is showing us aspects of ourselves, reminding us of embarrassing encounters, judgement errors, deceits in our own lives. Also of touching moments and the infinite capacity of some people to express their humanity and to acknowledge yours.

Maybe it’s time to pull Dance of the Happy Shades off the shelf for another read?

- Reg Sauvages

Reginald Sauvages, PhD, is the nom de plume of a local bibliophile (read: bookworm) who goes on building bookshelves and buying paperbacks for the beach so sand doesn’t ruin favourite clothbound books, even while owning an e-reader.

Religion for Atheists

Alain de

Botton

This work of genius is a powerful bridge between religious believers and the secular world. In Religion for Atheists, Alain de Botton delivers a carefully written and well-structured guide to the success religions have had over the centuries connecting with people and promoting the growth of their body, mind, and soul. Touching on areas ranging from community, tenderness, pessimism, and perspective to art, architecture, and institutions, de Botton exposes a wealth of knowledge that seemingly has been overlooked by the growing secular world.

While this book is clearly directed at atheists, perhaps those who are religious have just as much to gain from this read. It may remind church goers, for example, why in fact they go to church. Regardless, if readers put their egos aside before reading this book, they will find themselves compelled by de Botton’s presentation of a happier, more positive, and much more prosperous way of life, as opposed to denigrating the religions from which the knowledge necessary to lead such a life is drawn.

For those expecting a dry read, Religion for Atheists is neither life-sucking nor yawn-inducing. Relevant and interesting, if the secular world had a Bible, this would be it. As de Botton states,

This work of genius is a powerful bridge between religious believers and the secular world. In Religion for Atheists, Alain de Botton delivers a carefully written and well-structured guide to the success religions have had over the centuries connecting with people and promoting the growth of their body, mind, and soul. Touching on areas ranging from community, tenderness, pessimism, and perspective to art, architecture, and institutions, de Botton exposes a wealth of knowledge that seemingly has been overlooked by the growing secular world.

While this book is clearly directed at atheists, perhaps those who are religious have just as much to gain from this read. It may remind church goers, for example, why in fact they go to church. Regardless, if readers put their egos aside before reading this book, they will find themselves compelled by de Botton’s presentation of a happier, more positive, and much more prosperous way of life, as opposed to denigrating the religions from which the knowledge necessary to lead such a life is drawn.

For those expecting a dry read, Religion for Atheists is neither life-sucking nor yawn-inducing. Relevant and interesting, if the secular world had a Bible, this would be it. As de Botton states,

God may be dead, but the urgent issues which impelled us to make him up still stir and demand resolutions which do not go away when we have been nudged to perceive some scientific inaccuracies in the tale of the seven loaves and fishes. The error of modern atheism has been to overlook how many aspects of the faiths remain relevant even after their central tenets have been dismissed.For a quick look at de Botton's ideas, see his TED talk on Atheism 2.0:

- Joe Cassidy

Games Primates Play

Each chapter in Games Primates Play focuses on a

specific aspect of human behaviour (i.e., competition, favoritism, dominance and

so forth). Although the chapters contain some scientific information about their

respective behaviours, the meat of the chapters consists of vivid examples of

the ways that non-human primate behaviour is reflected in modern human

behaviour. By using specific examples, Maestripieri is able to illustrate the

exceptional complexity of many primate societies. The connections he draws

between humans and the “games primates play” are not far-fetched; rather, they

are informative, unexpected, and surprisingly hilarious. I particularly liked

the section “We are all Mafiosi” in chapter three, where Maestripieri draws on

his experience with the nefarious Italian academic community to speak about

favouritism, nepotism, and mob culture in human and primate societies.

What I especially liked about Games Primates Play was that each chapter could easily stand alone. Each was an interesting snapshot of human nature, much easier to digest than a continuous scientific narrative.. This meant that I could put down the book after a chapter and return to it without missing or forgetting details.

What I especially liked about Games Primates Play was that each chapter could easily stand alone. Each was an interesting snapshot of human nature, much easier to digest than a continuous scientific narrative.. This meant that I could put down the book after a chapter and return to it without missing or forgetting details.

Ironically, my favourite

part of this book was the epilogue. By concluding the book with an incredibly

poignant and relevant story, the epilogue concisely and eloquently situates the

book within its proper context. This book is not meant to reveal the meaning of

life, nor does it make any value judgments about the goodness or badness of the

primate or human relationships described throughout. The real purpose of this

book, and where I think it ultimately succeeds, is to simply illustrate our

relationship with primates and to show, for better or for worse, what human

nature really is.

See Maestripieri's RSA talk on some of the ideas in his book:

- Michelle Hunniford

See Maestripieri's RSA talk on some of the ideas in his book:

- Michelle Hunniford

Monday, April 1, 2013

If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho

If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho

Translated by Anne Carson

In

one of those coincidences you sometimes finding yourself wondering about, I

opened Anne Carson’s magnificent translation of Sappho’s poetry to these lines:

Some men say an army of horse and some men say an army on footSappho’s statement counters our daily news, and Homer’s epic news. In The Iliad the old men on the walls of Troy look out over the fields of battle and judge that, so far, the ten noble years of bloodshed and suffering in the Trojan War have all been worth it in order to possess Helen and her “terrible beauty,” as they put it. But war is not the most beautiful thing, and Sappho’s certainty about it resonates for us.

and some men say an army of ships is the most beautiful thing

on the black earth. But I say it is

what you love.

The

resonances begin with a book design that stops you before you open the pages.

Wrapped around the spine, and resting in the white open space of the cover,

lies a torn and broken papyrus fragment. Greek letters creep uncertainly over

the ragged fabric and you find yourself holding so much emptiness in your

hands. Surfacing out of this terra incognita, the first words on the

cover appear: If Not, Winter. If not what? If not love? Then winter

comes? This is probably the kind of sentimental speculation that Carson would

dismiss.

All

we know is “if not, winter.”

These three words stand alone in one of the fragmentary love poems inside. The

rest is silence. The other poems, sometimes no more than just a few words on a

blank page, extend the sense of loss and uncertainty. Reading them is like

seeing dream fragments surface out of the great emptiness of Sappho’s distance

from us. And like the best dream fragments, the poems are loaded with meanings

that begin to coalesce.

Sappho's lyric poetry is presented in discrete pieces that suggest as much as they

reveal. Carson reveals more in her notes. They fill in some of the absence that

is present in the space on most pages. Sappho’s poem about life in exile with

her daughter and Carson’s sensitive commentary were published in a longer

version in Men in the Off Hours. Here they are again, filled with the

love and sorrow of a mother who, in her exile, cannot care properly for her

daughter. Carson deepens our understanding of this maternal sadness with a

dense commentary that opens up the experience of Sappho’s cultural location,

and of her dislocation in exile. At other times, Carson's notes are full of blunt

good sense. In response to today’s adolescent obsession with sexual preference,

she states, “It seems that she knew and loved women as deeply as she did

music,” and then asks dismissively, “Can we leave the matter there?”

Of

course Sappho is, above all, a poet of love. Some of her songs of love for her

lovers, daughter, brother, and friends feel like they could have been written

yesterday. Did Van Morrison take a look at this two-line fragment before he

wrote "Crazy Love"?

you came and I was crazy for you

and you cooled my mind that burned with longing

Does

this recall The Commitments' "Try a Little Tenderness"?

and on a soft bedIn a similar way, the fragments, empty space, and broken lines conspire to let loose, probably with more restraint, our longing as well. Our longing for more of Sappho’s work begins to recover, through this unusual book, our own experiences of loss. It’s a little like trying to remember, from a distance, just how much you loved someone before they were gone. It is also a relief to have Carson’s reconstruction and translation, and to see these images now, as the descendants of The Mechanical Bride threaten to metastasize the untrustworthy oracles of digital space.

delicate

you would let loose your longing

The

translator’s biographical note reads, as usual, “Anne Carson lives in Canada.”

This seems like another fragment, although Carson does appear on stage in her

introduction, before not quite disappearing into the wings: “I like to think

that, the more I stand out of the way, the more Sappho shows through.” Her

introduction and notes have kept me re-reading these fragments, and the reward

is that Sappho does show through. With winter behind us, you could open this

book some spring morning as “just now goldensandaled Dawn” (fragment 123) rises

in the east, and know that “the most beautiful thing on the black earth…is what

you love.” Otherwise, “if not, winter.”

-

Jim Reid

Jim Reid has seven years of Latin, and no Greek. He has been waiting for

another translation of Sappho since he picked up Mary Barnard’s in 1973.

The Emperor of Paris

C.S. Richardson

C.S. Richardson’s follow-up to his widely

praised The End of the Alphabet is an enchanting, handsomely crafted,

romantic fairy tale set in the City of Light in the early years of the

twentieth century. Through its two main characters—the illiterate son of a

baker and a scarred girl with a passion for paintings—The Emperor of Paris

fascinatingly explores the allure of storytelling and imagination from multiple

angles. Though the two protagonists seem to live in separate spheres, they are

destined to meet. Booksellers, shopkeepers, vagrants, and war veterans populate

an urban realm in which they forge ahead along their interconnected paths,

constantly searching for sustenance, security, and meaning. Richardson balances

his multiple plotlines, scope across history, and well-developed characters

with a honed sense of delicacy and skill that continually rewards his lucky

readers with its elegance and freshness. This sleek, light, thoroughly

enjoyable gem of a novel will surely emerge as one of the year’s top literary

delights.

Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending

Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending

Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton

The colourful cover with a happy face hiding behind an American coin immediately caught my attention. I was also intrigued by the title and assumed that Happy Money would not be the typical money book filled with budgeting and investment advice.

I was not disappointed.

Using light and entertaining voices, behavioural scientists Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton demonstrate how money can buy happiness—if you spend it right. These are their five core principles:

- Buy experiences.

- Make it a treat.

- Buy time.

- Pay now, consume later.

- Invest in others.

The ultimate goal is to wring the most happiness out of every dollar and to apply as many principles as possible to each money transaction.

I was impressed by the Starbucks example: In a controlled study, three different groups were given $10 Starbucks gift cards. The authors discovered that the people who were asked to take their friends out for coffee were happier than those who had treated themselves or simply given the cards away. Investing and connecting provided the most bang for the buck. To reap even more happiness, the authors suggest that you pay up front for the card at the beginning of the week, putting in enough money to buy a basic coffee, Monday through Thursday, and a Frappuccino on Friday. Offer to treat a different friend each day and accompany them to Starbucks.

See Michael Norton's TEDx talk below on the book's findings. Definitely food for thought.

- Joanne Guidoccio

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)